The Sycophant Economy

The fan in my room has developed a new sound. Not the old comfortable squeak that has been narrating my life since the Vajpayee years, but a kind of loose metallic chuckle, as if it has finally understood the cosmic joke and is now laughing at me, personally, while flinging stale winter air around this little room on the northern fringe of Kolkata. The TV in the corner is muted, the subtitles crawling across the bottom like a tapeworm of half-truths: MARKETS CHEER AI SURGE, TRUMP CAMPAIGN SAYS, JOBLESS CLAIMS, WAR, GROWTH, PATRIOTISM, “ATMANIRBHAR,” and whatever other talismanic syllables are required to keep the citizenry hypnotized between advertisements for fairness cream and low-interest EMIs.

I am fifty, bipolar, unemployed, un-licked and un-licking, contemplating whether to get up and make tea or simply merge, molecule by molecule, with the mattress.

The question that keeps circling like a diseased vulture over this scene is stupidly simple and unreasonably heavy: what exactly am I supposed to do now? Not in a vague philosophical “meaning of life” way. In the boring, bank-balance, rent-paying, food-buying way. Which, as it turns out, is the only meaning of life the system recognizes.

The Sycophant Economy

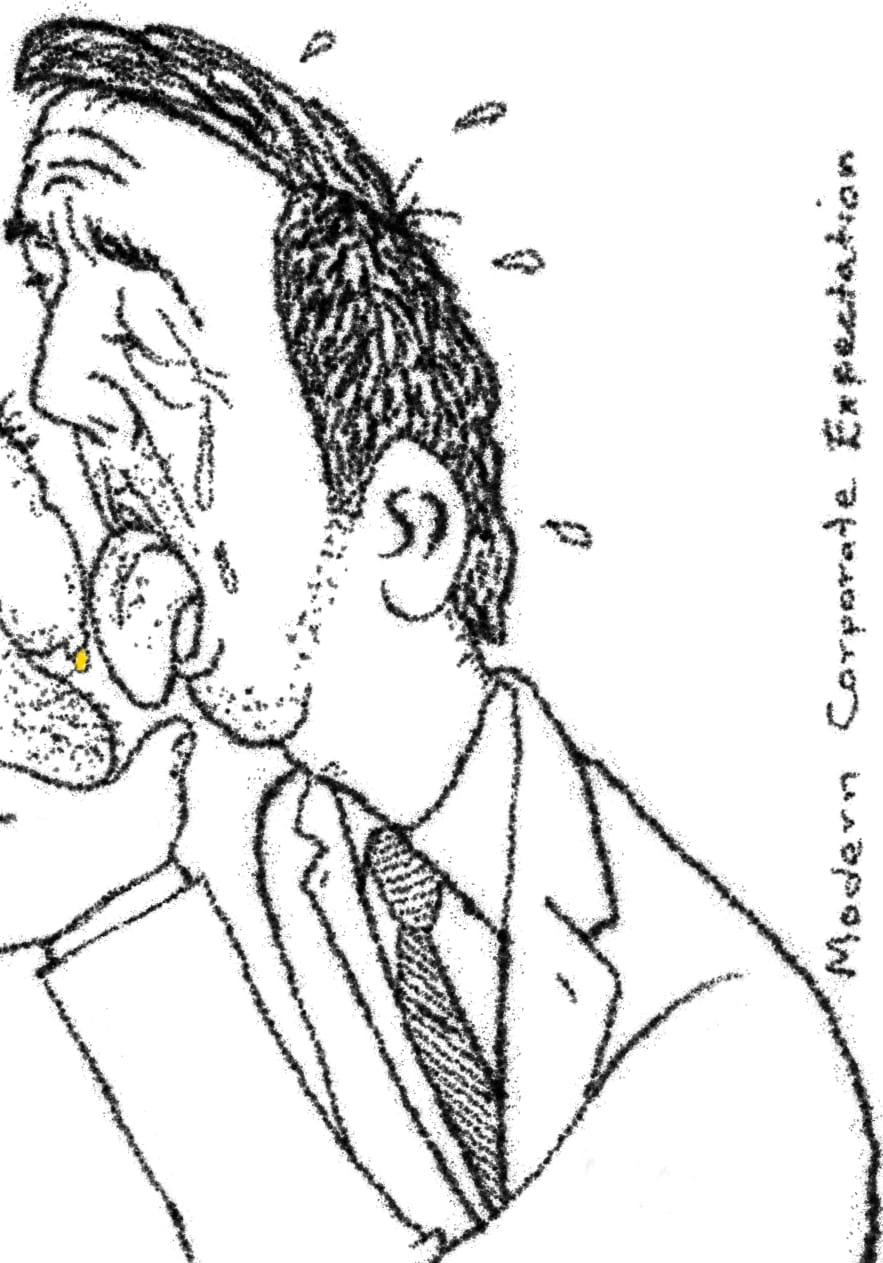

Somewhere along the way I realized—late, like most of my realizations—that modern life is basically a very elaborate audition to see who can most convincingly polish the nearest powerful derrière with their tongue while reciting corporate mission statements or patriotic slogans without retching.

We don’t call it that, of course. We call it “networking”, “mentorship”, “executive presence”. In India, the words are “jugaad”, “setting”, “source”. In university brochures they say “interpersonal skills” and “team player”. In practice, it’s a sorting mechanism for who can shape their face into the most agreeable configuration while their internal monologue screams.

I used to be able to do a passable imitation. Twenty-something me, freshly exported from a north Calcutta lane where the biggest career advice you got was “become engineer or become nothing”, could stand in an American conference room, nod wisely at mediocre PowerPoint slides, and say things like “that’s an interesting direction” instead of the more accurate “this is warmed-over porridge for the brain”. I could even laugh at the boss’s joke, the ultimate test of adaptability.

Now, the very idea of doing the same routine again fills me with a kind of full-body urticaria. There’s a point in life where the mask fuses to the face, and if you try to pull it off, the skin comes with it. I appear to have reached that point without the compensating benefits—no stock options, no beachfront property, only the stripped face.

I blame age, obviously, and the bipolar brain chemistry, but also the sheer scale of dishonesty required now. The volume knob has gone from “polite hypocrisy” to “sustained performance art”.

Small Brain in a Big Circus

Part of the problem is that I grew up taking words seriously. Not nobly, not in a Gandhi-ish, starched-khadi moral way, but in the narrow, nerdy way of a boy who had more conversations with books than with people. You tell me “I’ll call you back,” my brain, ever the literal clerk, writes it down in the ledger. You say “we’ll explore opportunities,” the same clerk notes: “investigate options soon.” When it turns out “I’ll call you back” means “I will never think of you again unless I need something” and “we’ll explore opportunities” means “I am ending this conversation gently so that your gluteus maximus leaves my chair,” there is a small but non-trivial dissonance.

Multiply this by decades.

Add to that the peculiar spice-mix of bipolarity, where on some days I feel like I could design a new economic system before lunch and on others I do not feel qualified to operate a toothbrush, and you get the perfect recipe for paralysis. In hypomanic phases I think, Fine, I’ll write, I’ll teach online, I’ll build a thing, I’ll explain determinants to the world, I will finally connect all these stray wires in my mind into one coherent contraption. In depressive phases, I look at the same wires and think, This is just e-waste with delusions of grandeur.

Between these oscillations sits the job market, smug as a cat, demanding cheery LinkedIn posts and proof that you are “excited to join our dynamic team” of people slowly evaporating into performance dashboards.

The Fig-Shower Tradition

There is a Greek word at the root of this circus: sykophantēs. Literally, “fig-shower.” One theory is that these were the people who informed on smugglers of figs in ancient Athens; another idea is that it was some salacious gesture involving the hand that looked vaguely like a fig and presumably insulted somebody’s lineage. Scholars disagree, as they often do when the past refuses to cough up clear evidence. What matters is how the word mutated.

From fig police it became “informer,” then “flatterer,” then the modern sycophant: the one who lives on the oxygen supply of someone else’s power. You see them in every corridor: the junior bureaucrat vibrating with eagerness when the minister walks by, the corporate deputy who laughs half a second too loudly whenever the CEO says anything, like a built-in laugh track for the powerful.

Once upon a time, societies at least had the decency to admit this was disgusting. Court jesters mocked kings, satirists bit ankles, philosophers muttered in corners. Now we have influencer culture and “personal branding.” You are supposed to broadcast your allegiance to the nearest authority, whether it’s a political cult, a corporate cult, or the cult of Self-As-Startup. The fig-shower became the fig-inserter, carefully feeding the king’s ego its daily portion of sweetness.

I, unfortunately, have terrible fig-handling skills. I tend to point at the fruit and say, “This looks rotten,” which is not a career-advancing remark.

Export-Quality Human, Recalled

In 1998, leaving this city felt like the only rational move. The air already smelled of exhaust and slow failure, and my generation had been trained like obedient lab rats to run toward America whenever the maze doors opened. America then was still selling itself as the land of rational institutions, clean streets, and meritocracy—yes, there was racism and inequality, but there was also the white steel cleanliness of campus libraries open till midnight and supermarkets where the cheese aisle alone had more options than my entire childhood.

For a brown, short, unremarkable man with decent English and inflated dreams, it felt like stepping into the textbook illustrations of “developed country”. You could get on a bus and it actually arrived roughly when it said it would. People queued. Strangers said “excuse me.” The police did not automatically look like they were auditioning for the role of corrupt villain in a B-grade movie.

Fast-forward to the Trump era, that great orange stress-test of American institutions, and suddenly the metaphorical underpants were visible. The country that had lectured the globe on democracy now revealed its own deep love of demagogues, tribalism, and televised hysteria. You could practically see the reality-show cameras hovering above Congress. The phrase “leader of the free world” started to sound like something written by a drunk copywriter in 1952 that nobody had bothered to update.

I watched this decay from a distance and in person—airport security that looked at you a beat too long, news channels mutating into carnival barkers, social media turning everyone into unpaid marketing interns for their own lives. The America that once symbolized “escape” now seemed like an enlarged, neon-lit version of the same circus we run back here, only with more guns and better highways.

It is not that America suddenly became awful; it is that the mask slipped just enough for a former worshipper like me to recognize the family resemblance. The same Homo sapiens: easily panicked, easily manipulated, eternally convinced of being exceptional.

And now, of course, AI is the new exceptionalism.

The Slow Asteroid

People like to compare climate change to a “slow-motion disaster,” which is accurate but optimistic. AI is the sibling meteor: you can’t see it from the balcony, but you can feel the air pressure change.

The old asteroid, the one that ended the Cretaceous, did its work with admirable efficiency: rock from space slams into earth, dinosaurs go from apex predators to future petrol, a new era begins. If you’re going to be wiped out, that’s at least narratively satisfying.

This new digital asteroid is less cinematic. It is a billion lines of code, a trillion parameters, humming away in data centers, learning to do in seconds what whole swarms of humans used to do for rent and grocery money. First the simple things—transcription, summaries, boilerplate emails—then more complex things, like writing essays that sound uncomfortably like something I would write on a good day, or detecting patterns in images that radiologists used to get paid real money to interpret.

On TV, the talking heads wobble between reassurance and doom. “AI will create new kinds of jobs,” they chirp, as if everyone in a call center today will be tomorrow’s “prompt engineer” and nobody will be quietly discarded like obsolete hardware. There are charts, there are policy papers, there is earnest chin-stroking.

In my room, the fan laughs.

Because I can see, with the unhelpful clarity of bipolar pessimism, that the people who most loudly proclaim AI as humanity’s next step are often the same type who happily used older technologies to compress salaries, outsource risk, and turn the average worker into a replaceable widget. Why would they suddenly grow a conscience because the new tool happens to be cleverer?

Of course, I also see another truth, less dramatic and more humiliating: I am not special enough to be exempt. My skills—words, analysis, pattern-spotting, teaching—are precisely the sort that these large stochastic parrots are skewering and roasting over a bonfire of venture capital. I have dedicated my life to knowledge, and knowledge, the market informs me, is now a freemium product.

So again the question: what do I do?

The Misfit’s CV

Imagine, for a moment, the honest version of my résumé.

Name: Irrelevant, but Bengali, middle-aged, intermittently functional.

Education: Too much, in the wrong directions, at the wrong times.

Skills: Reading dense books, explaining difficult ideas, sniffing out nonsense, refusing to flatter hierarchies, long-form brooding.

Weaknesses: Everything the world currently rewards.

Explain that to an HR algorithm.

The official world wants a narrative: upward trajectory, clear brand, “passion for innovation”, tidy story. My story is not tidy. It is constellational—clustered around obsessions, detours, breakdowns, abortive restarts. I can give you a passionate lecture on the history of asphalt, the etymology of “parliament”, or why bitumen behaves the way it does under load cycles, but I cannot convincingly pretend that uploading slide decks to SharePoint is my life’s calling.

In the older world, there was sometimes a small crooked lane for such people. Academia, maybe, or research departments, or eccentric small firms where the patriarch valued oddballs as a kind of lucky charm. Not great, not reliable, often exploitative, but at least there was a sliver of space for misfits.

In the current algorithmic economy, that lane is being sealed off. You are either a “resource” or you do not exist. Employers don’t say “we’re not hiring weirdos,” they say “cultural fit” and “communication style” and “team alignment.” It boils down to the same thing: can you smile without baring your teeth?

I cannot. Or rather, I can, but every year it feels less worth the dental strain.

Bipolar Optics

Then there is the brain, this unreliable narrator in my skull.

Psychiatrists like to talk in charts and checklists: manic episodes, depressive episodes, mixed features. From the inside it feels more like standing in a room where the lighting technician keeps changing the bulbs without warning. One day the room is bright, golden, and everything is possible. I can script a future, design three projects, plot ten essays, resurrect my career, revolutionize something or other. The very next week the same room is lit by a single flickering tube light, buzzing like a mosquito, making everything look cheap and pointless.

The external reality doesn’t change: same bank balance, same city, same headlines, same ageing parents, same multiplying stray dogs on the street. But my appraisal of what is doable shifts wildly, and I, like an idiot, keep believing whichever mood is currently holding the microphone.

This makes long-term planning difficult. On an elevated day I flatter myself: of course I can navigate this AI tsunami, I’ll find a niche, I’ll teach the machines to teach humans, I’ll start a thing in Bengali for kids, no, for adults, no, for the failed geniuses of the third world, there is a whole market! Then my mind, obedient horse that it is, gallops off into details—domain names, curricula, monetization models.

On a flattened day, I look at the same notes and think: this is deranged. It presupposes that I can repeatedly get out of bed, withstand small talk, and endure the indignity of marketing myself in an attention economy designed by silicon-valley-trained sadists. It presupposes energy I simply do not have consistently.

So I end up here, in this room, fan laughing, cursor blinking, neither starting nor entirely giving up, hovering like a malingering ghost between intention and execution.

Complicity, or the Frog That Stayed

It would be very convenient to blame everything on “the system”—capitalism, fascism, Trump, Modi, Silicon Valley, colonialism, astrology, take your pick. And certainly, these forces matter. I am not hallucinating the corruption, the mediocrity in high office, the structural unfairness that makes some lives a perpetual lottery of survival while others worry about choosing the right shade of imported marble.

But if I am honest—and if there is one pointless virtue I still cling to, it is this compulsion toward honesty—then I must also admit my own part.

I stayed. I watched things deteriorate and I stayed. I knew, as early as my twenties, that I was allergic to certain forms of obedience, and yet I tried to play the game, half-heartedly, hoping some benevolent hand would spot the misunderstood mind and place it somewhere safe. I let opportunities slide because I did not want to grovel; I also did not build alternatives because that required a stamina I didn’t cultivate. I sneered at the performers, but I also envied their results.

I like to think of myself as someone who resists flattery and refuses to flatter, a proud little porcupine with intellectual quills. But the truth is less heroic. I am also lazy, frightened, vain. I want recognition without grovelling, security without submission, meaningful work without tedious compromise. I want the world to rearrange itself around my peculiarities while I sit here composing baroque sentences about its failures.

There is something both tragic and very funny about that.

The Noise and the Mute Button

What makes this particular historical moment uniquely unbearable is the sheer volume of performative lying. Not the existence of lies—that is an old human hobby—but the omnipresence, the 24x7 surround-sound.

Political leaders stand in front of cameras and confidently state things that are contradicted by video clips from three months ago, and the anchors nod like dashboard dolls. Corporate heads talk about “family culture” while quietly preparing the next restructuring to chop off the bottom twenty percent. Tech evangelists proclaim AI will free humanity from drudgery while quietly turning every creative field into a gladiator arena where you are expected to produce twice as much for half the pay, competing with your own training data.

In this environment, someone like me—overly literal, pathologically unable to play along convincingly—starts to feel not only useless but slightly mad. If the whole village is applauding the emperor’s new clothes and you keep pointing at the shimmering nudity, after a while you begin to wonder whether you’re the one hallucinating.

So, most days, I mute the TV.

Not metaphorically; literally. The remote is within reach, my fingers know the route. The anchors open their mouths and out comes silence. I read the subtitles, which is somehow less offensive, like being insulted by a mime rather than a loud drunk.

I scroll less than before, though not as little as I would like. The doom-scroll reflex is a kind of mental eczema: you know scratching makes it worse, but the itch is real, the temporary relief seductive.

Writing, when I manage it, becomes the only activity that feels even vaguely like resistance. Not grand resistance—nobody is toppling any government because I compared the job market to a malfunctioning lavatory—but a small, stubborn assertion that my version of reality exists, however unfashionable. That my confusion and disgust and small kindnesses are data points too.

So, What Now?

The original question remains on the table like an unpaid bill: what will you do, sir?

The honest answer, for once, is simple and disappointing: I don’t know.

I can list possibilities like a bored astrologer: maybe I will teach some children down the lane, borrowing their schoolbooks and smuggling in real explanations between exam cramming. Maybe I will manage to turn this torrent of angry essays into a book so niche that only twelve people ever read it, all of whom will write me emails beginning with “I thought I was the only one who felt this way.” Maybe I will stumble sideways into some small role in this AI carnival—curator, translator, explainer for those who still want a human voice in the loop.

Or maybe I will simply continue like this for a while longer: a slightly deranged commentator in a small room, oscillating between wild schemes and complete inertia, watching the slow asteroid glow brighter in the collective sky.

There is no neat arc here, no “and that’s when I realized my true calling” revelation. Life, as experienced from this particular ageing Bengali body with its unreliable neurotransmitters, does not offer that kind of cinematography.

What I have, instead, is this moment: muted TV, laughing fan, the faint smell of someone burning trash somewhere in the lane, the soft hum of distant traffic that sounds, if you squint your ears, like the ocean in a cheap conch shell. My fingers hovering over the keyboard, indecisive between opening a job portal, a textbook, or yet another blank document.

For now I do the easiest, most pointless, most essential thing I can manage: I add one more sentence to this pile, then another, as if words themselves were a small, rickety barricade against the flood.

Later, I’ll probably delete half of it. Or all of it. Or I won’t.

The fan keeps laughing. I reach for the remote, not to turn the TV on, but to make sure it stays exactly as it is: lighted, silent, mouthing its nonsense to nobody in particular, while I sit here in my little pocket of voluntary static, a misfit meteorite that somehow forgot to burn up.