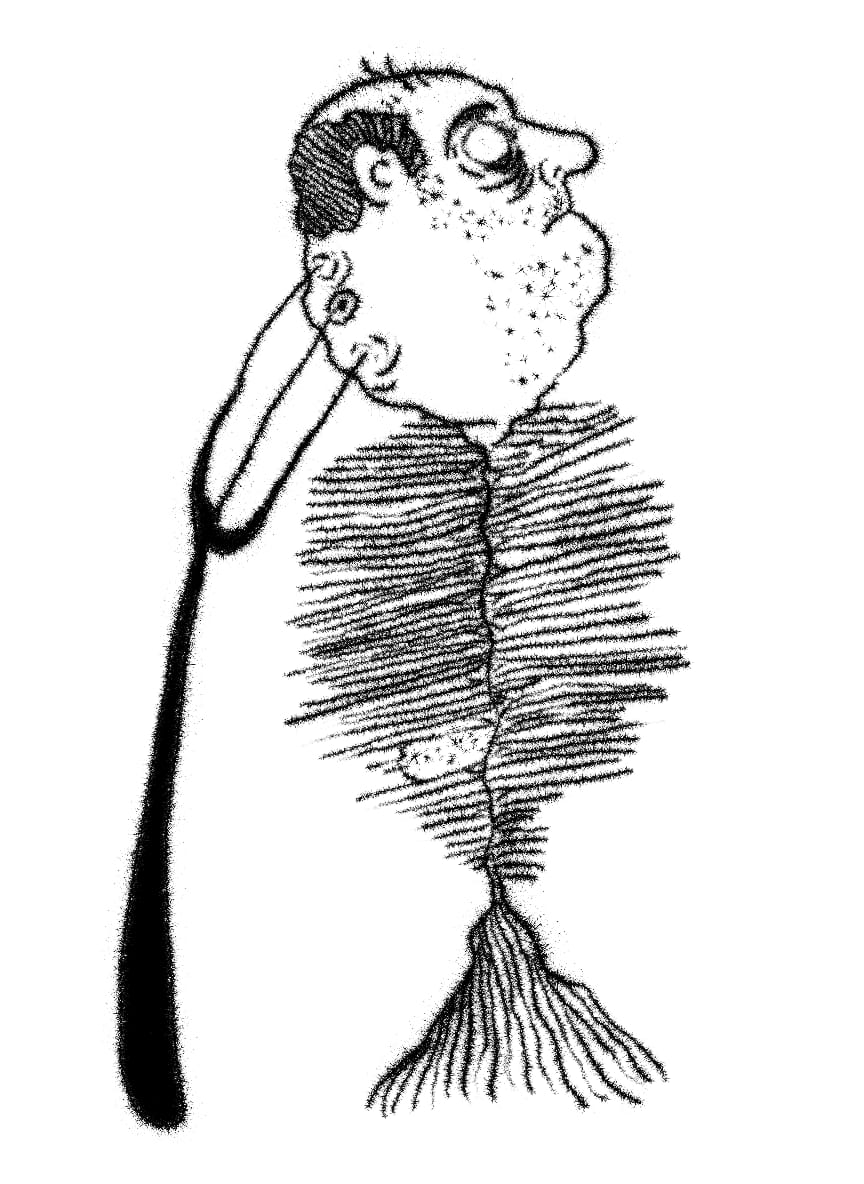

Fish Bones

There is a particular kind of silence that falls over a Bengali dining table when the fish arrives, the way a courtroom quiets when the judge enters, or a railway platform pauses just before the train finally pulls in; even the ceiling fan seems to develop a conscience and stop rattling for a second, as if it too respects the ritual of maachh and bhaat.

On my childhood table the fish would appear in a metal bowl, steaming, aromatic, and sinister, like a friendly-looking visiting relative who you know is going to ask about your exam marks. The adults would lean in, eyes trained in the ancient art of deboning, their fingers moving with the unhurried efficiency of veteran surgeons; my role, as a scrawny, easily-traumatized boy, was to sit very still and attempt not to die.

Because somewhere between the third mouthful and the inevitable second helping, there would come that moment: a sliver of bone, translucent and treacherous, sliding past the tongue’s radar and lodging itself halfway down the throat. The next few seconds were always the same – the sudden panic, the coughing fit, the watery eyes, the thumping on the back by a relative who believed the human respiratory system could be repaired by percussion, and the chorus of reassurances: “Ektu bhaat kheye nao, chole jabe” – which is Bengali for, “Swallow some rice and we’ll see.”

You survive, of course. Children are resilient and apparently designed to be proof-of-concept prototypes for bad domestic hazard management. But something in the brain takes notes; some little cluster of neurons, doing their tedious Bayesian updates in the background, quietly raises the estimated probability that “fish with many bones” equals “imminent tracheal apocalypse,” and from then on, that’s that.

Fast forward some decades and I am a fifty-ish, chronically underachieving, over-educated Bengali who likes fish in principle, in theory, in cultural alignment, but prefers in practice only those varieties that present a minimal chance of turning my dinner into an impromptu Heimlich tutorial. Give me the fillets, the neat steaks, the boring, low-risk species, the piscine equivalent of those soft-spoken people who will never ask you what your salary is or make you join a WhatsApp group.

The rest – the legendary, bony, spine-with-flesh-attached types – I approach the way a traumatised soldier regards fireworks.

Of course, this is not really about fish.

Bones as Policy

There is a smug sentence you hear growing up in Bengal: “Maachh-bhaat-e Bangali” – the idea that a Bengali is essentially constructed from fish and rice, like some aquatic version of Homo sapiens uniquely optimized for monsoon, mildew, and moralizing. As with most identity slogans, it is charming and mildly fascistic at once: a mix of nutritional fact, cultural habit, and the usual pressure to conform. Love fish, they say. Love fish this way, in this configuration, with these bones and these rituals and this frightening aunt who polices whether you’re eating the head respectfully.

When I say I like fish but prefer the ones with fewer bones, I can almost hear an invisible jury of ancestors tutting. To dislike bones is, in some circles, to confess a lack of character, the same way not liking football makes you suspect in other cultures. There is a puritanism to it: if you don’t endure the bones, do you really deserve the taste?

You can see the same philosophy in Indian education. If you don’t swallow the entire bony structure of the syllabus – the pointless derivations, the badly explained theorems, the moral science lectures stuck between physics chapters like fish bones in curry – you are somehow less worthy of the degree. The idea that learning could be deboned, filleted, made more digestible without losing nutrition is treated as decadent, Western, suspiciously student-friendly.

The British, of course, had a different fish in mind when they designed the whole apparatus. They wanted clerks – reliable, repetitive, grammatically house-trained – who could copy numbers and letters from one ledger to another without too many original thoughts getting stuck in the system. A clean boneless workforce, pre-processed and easy to swallow for the imperial digestive tract. The fact that we still swear by this system long after the original eater left the table is one of those postcolonial jokes that stops being funny once you realise your own life is the punchline.

Once Pricked, Avoid Shrubbery

My relationship with bones – fish or otherwise – follows a very simple algorithm: one memorable injury, then a lifetime of exaggerated caution. I get pricked once and my brain, like a badly tuned alarm system, decides that all shrubs are now suspect.

I choked on fish as a child, so now I audit fish like a nervous tax inspector. I had one particularly humiliating romantic disaster in my twenties, so I now approach adult relationships like they are unexploded landmines from a war I didn’t even fight in. A minor driving mishap, and I become a pedestrian philosopher for years, walking the city like a disgruntled Socrates who failed his driving test.

From a clinical perspective, this is just trauma plus an overactive risk-averse temperament. From the inside, it feels like my amygdala has unionised and is now over-performing its job, filing objections against everything with enthusiasm. The bipolar brain adds its own special effects to this; in a hypomanic phase I will briefly forget all the bones, all the near-chokes, all the disasters and rush headlong into some new project – a big idea, an impossible website, a grand life reboot – and then, as the mood slides back into the gently suffocating porridge of depression, the memory of every previous bone returns, each one annotated in HD.

The fish bone in the throat is an almost perfect metaphor for how I internalise discomfort: something tiny, objectively manageable, becomes lodged crosswise in perception. The rest of the world is shouting, “Just swallow some rice, it’ll go away,” while my entire sensorium is screaming, “The oesophagus is cancelled, we are going to die.”

So, over the years, I have reorganised my life in favour of soft food.

Not literally – I still eat crunchy things, my jaw hasn’t retired – but emotionally, socially, professionally. I prefer routine to novelty, solitude to social adventure, books to networking events, the safe glow of a laptop to any scenario involving name tags, handshakes, or open-ended questions like “So what do you do?” I have built, around my fragile, over-indexed fear circuitry, a shanty of habits, a small predictable shelter in the boondocks of North Calcutta, where the biggest daily risk is that the neighbour’s child will start practising Bollywood dance routines at full volume during my afternoon existential crisis.

The Hermit in the City of Ruins

“Boondocks” is a charitable way of describing where I live; it suggests a rustic charm, some greenery, maybe a goat. In reality it is more like a museum of urban neglect, a neighbourhood composed of half-finished ambitions, peeling walls, and a rotating cast of stray dogs who consider the entire lane their latrine and meeting hall.

I live in a modest flat whose chief architectural feature is that the walls don’t meet at quite the angles Euclid would have preferred. The ceiling fan makes a noise like a small helicopter fighting obesity. The view from the window is a tangle of cables, a patch of obstinate sky, and rooftops that look permanently surprised – water tanks, broken chairs, that one unfurling blue tarpaulin that has survived more monsoons than some local politicians.

Calcutta is famously always in ruins – not in the romantic, “faded grandeur” way tourism brochures try to sell, but in the more practical sense that something is always being built and never finished, repaired and never quite fixed, painted and immediately stained again by the traffic and the air. It is a city that seems to live in a permanent state of hangover from a colonial party it didn’t consent to host, mixed with a drunk, late-stage-capitalist carnival of consumption it cannot actually afford.

In this setting, my hermitage is not particularly dramatic. I’m not in a cave; I’m in a room with questionable plumbing and adequate Wi-Fi. But I have withdrawn in other ways: I rarely attend weddings (too many people asking “When are you…?” – fill in the blank with any life milestone I have failed to achieve), I avoid religious gatherings (my allergy to grandstanding and mythology is severe enough that it should be listed formally somewhere), and I treat phone calls like incoming asteroids.

I am, as I often joke, content with the contents of my own emissions – the smell of my own room, my own thoughts, my own digestive symphonies. This is not exactly aspirational, but it is honest. The world outside has too many bones; inside, at least I know where most of them are buried.

Boneless Religions, Bony Truths

Fish bones make good philosophy props. If you look at how societies feed their citizens narratives, you notice a pattern: the real world is bony, full of sharp facts, contradictions, uncomfortable trade-offs. The myths, on the other hand – the national myths, religious myths, civilizational bragging – are tender fillets served in thick gravy.

The stories we are asked to swallow about our glorious pasts, our spiritual superiority, our economic destiny, are often boneless to the point of being gelatinous. No hard questions, no structural analysis, just soft phrases repeated until they feel like facts. “Ancient wisdom,” “world guru,” “greatest democracy,” “family values,” “Make X great again” – it is all mashed into a paste that slides down the throat without obstruction, and if some inconvenient bone of reality – poverty, inequality, bigotry, corruption – gets stuck, the preferred response is not to remove the bone but to shout at the person choking.

In this sense, my fish-bone paranoia is oddly principled. I don’t trust boneless narratives; I assume the bones have been removed for a reason. I would rather see the skeleton, even if it scares me, than swallow a story that has been mechanically separated from its own structure. Fish, unlike ideologies, don’t lie about where their bones are; you can see the ribs, trace the spine. Human institutions are less considerate.

In America, where I spent some years between 1998 and 2014, I watched this boneless narrative industry blossom into something truly industrial. The country I first encountered was already full of contradictions – malls and homelessness, NASA and creationism – but there was still a sense that facts had some residual prestige. Over time, and especially under the orange-tinted carnival that followed, truth itself was filleted, repackaged, and sold as partisan fish fingers. Whole cable channels existed to ensure that no bone of reality disturbed the swallowing of daily outrage.

Back home, India was not far behind. We imported not just technology and fast food, but also the same algorithmic extraction of attention, the same weaponization of grievance, the same hunger for stories that flatter and absolve. Now we, too, are surrounded by boneless narratives about ourselves, some ancient, some new, many mutually contradictory, all demanding unwavering faith. To doubt them is to be labelled anti-national, anti-cultural, anti-whatever-the-current-keyword-is. In that climate, a person like me – sceptical, atheist, left-leaning, emotionally unstable – learns very quickly that it is safer to retreat to his room and negotiate with fish rather than with flags.

Biology of Avoidance

Psychology textbooks will tell you about conditioning, about learned avoidance, about how even a lab rat, after a few electric shocks, will choose to cower in the corner rather than explore. Human brains are fancier, more verbose, but not fundamentally different. I am essentially a talking rat who remembers too many shocks.

The first bone in the throat is a data point. The second one becomes a pattern. By the fifth, your nervous system has developed a policy: If X, then panic. In bipolar depression, the weighting of negative data is even more aggressive; every small failure is upgraded to an indictment of the entire self. “You cannot handle fish with bones” morphs seamlessly into “you cannot handle life,” which your overeducated prefrontal cortex immediately rewrites into something more eloquent and equally unhelpful, like “you are temperamentally unsuited to existence.”

So I construct a life of minimal X.

Minimal travel – complicated, expensive, full of risks, airports, strangers, lost luggage, and conversations with taxi drivers who ask “Business or pleasure?” as if there were any third category where I might fit.

Minimal romance – delightful, intoxicating, potentially catastrophic, full of bones disguised as dimples, and I have already proven remarkably unskilled at the deboning process.

Minimal ambition – everyone these days wants to be a founder, an influencer, an “AI entrepreneur”; I am content being a footnote, an ancestor of the machines, the human training data that never cashed out. Ambition, too, has bones: competition, humiliation, compromise, the need to talk to investors pretending to understand your idea while plotting your replacement.

My avoidance is not noble. It is not wise resignation. It is simply the equilibrium point of a nervous system that got pricked and decided shrubs were overrated. But unlike many people who lip-sync hustle culture while secretly exhausted, I at least admit out loud that what I really want, most days, is a cup of tea, a functioning fan, a decent book, and a plate of boneless fish that cannot surprise me.

Overeducated, Underseasoned

There is a special category of failure that comes from being overeducated and under-pragmatic. I have accumulated degrees, skills, and information the way some people collect stamps or scented candles – as if knowing more would automatically translate into living better. It does not. It simply gives you more vocabulary to describe your stagnation.

I know, for example, the approximate structure of a neuron, the fuzzy outlines of Bayesian inference, the etymology of “hermit” from Greek erēmitēs, meaning “of the desert.” I understand, at least in outline, how capitalism creates both smartphones and slums, how colonialism baked inferiority and aspiration into our middle-class DNA, how social media algorithms amplify the worst of our impulses. None of this knowledge has stopped me from becoming a reclusive middle-aged man in a noisy lane, occasionally arguing with a lizard on the wall about who pays rent.

The fish on my plate is sometimes the most concrete decision I make in a week. Bony or boneless? Risk or safety? Nostalgia or practicality? Do I honour my identity as a Bengali by wrestling with an ilish full of treacherous architecture, or do I quietly choose the bland, well-behaved fillet imported from some overfished river god-knows-where?

Most days, I choose the safer option. Some days, usually when the hypomanic current is whispering, “life is short, cholesterol is a social construct,” I will order the dangerous one. The first bite is glorious – the taste, the memory of childhood, the illusion of being part of a larger story – but by the third bone my throat has staged a coup, and I am back to square one, negotiating with my internal alarm system like a hostage-taker who forgot his demands.

Smallness as Strategy

It is fashionable now to talk about “living your best life,” a phrase that makes me want to lie down on the floor and evolve into a different species. My life is not “best” by any widely advertised metric – not financially, not professionally, not romantically, not geographically. It is best only in the very narrow sense that it is currently the only one I have managed not to abandon.

I live small, because big life requires big bones, and my throat is thin.

Some people climb mountains; I clean my desk. Some start companies; I figure out a slightly better way to arrange the books I own and will probably never fully read. Some travel the world; I make a cup of tea and stare at the patch of sky framed by cables, watching the clouds drift like absent-minded whales.

There is, buried in this smallness, an element of quiet rebellion. The world, especially the version of it wired into smartphones, demands constant expansion – more content, more followers, more hustle, more output, more visibility. To withdraw, to choose privacy, to be content with one’s own digestive byproducts and second-hand books, is not just cowardice; it is also, in a minor, ridiculous way, a refusal. I am not providing my life as entertainment content. I am not giving the algorithm my bones.

Of course, this is the heroic interpretation. The less flattering one is that I am just scared, lazy, and melancholic, and I prefer to spin that as “minimalist philosophy” instead of “unresolved therapy homework.” Both can be true. In my more lucid, depressive phases, I can hold this duality without flinching: I am both victim and accomplice, both products of history and manufacturer of excuses.

Ending, Or Something Like It

There is a single fish bone on the edge of my plate as I type this in my head – not literally, the laptop would protest – but imaginatively, there it sits, small, glistening, curved, a tiny sculpture of all the times I have let discomfort dictate architecture.

I could throw it away, let the maid sweep it into the city’s digestive system, where it will join plastic wrappers, pan stains, and the general evidence of our civilisation’s inability to tidy up after itself. Or I could keep it, in some little box, as a relic, a reminder of all the spines I have avoided – career, love, risk, confrontation – in the name of not wanting to choke again.

I will do neither. I will do what I usually do: push the plate away, pour myself another cup of tea, open a book I have already read twice, and tilt my chair towards the reluctant breeze from the window. Outside, somewhere in the lane, a hawker will shout about fresh fish, promising taste and tradition and today’s price.

Inside, I will sit with my boneless lunch and my bony thoughts, in a city half-collapsed and half-refusing-to-die, and try not to swallow anything I’m not prepared to live with for years.